What Does Enabling Mean?

A Guide for Families

You're not trying to hurt them. Every check you've written, every excuse you've made, every time you've smoothed things over with their boss or their landlord or their probation officer, you were trying to help. You were trying to buy them time. You were trying to keep them alive long enough for something to click.

So why does it feel like the harder you try, the worse things get?

This is one of the most painful questions families face. Where is the line between supporting someone you love and enabling the very behavior that's destroying them? The confusion is understandable. Love wants to protect. Love wants to rescue. And when someone you raised or married or grew up with is drowning, every instinct screams to jump in after them. The problem is that sometimes jumping in just teaches them they don't need to learn to swim.

What Enabling Actually Means

Enabling, in the context of addiction, means removing the natural consequences that might otherwise motivate someone to change. It's not about intent. It's about effect. You can love someone deeply and still enable them. In fact, the people who enable most are usually the ones who love most.

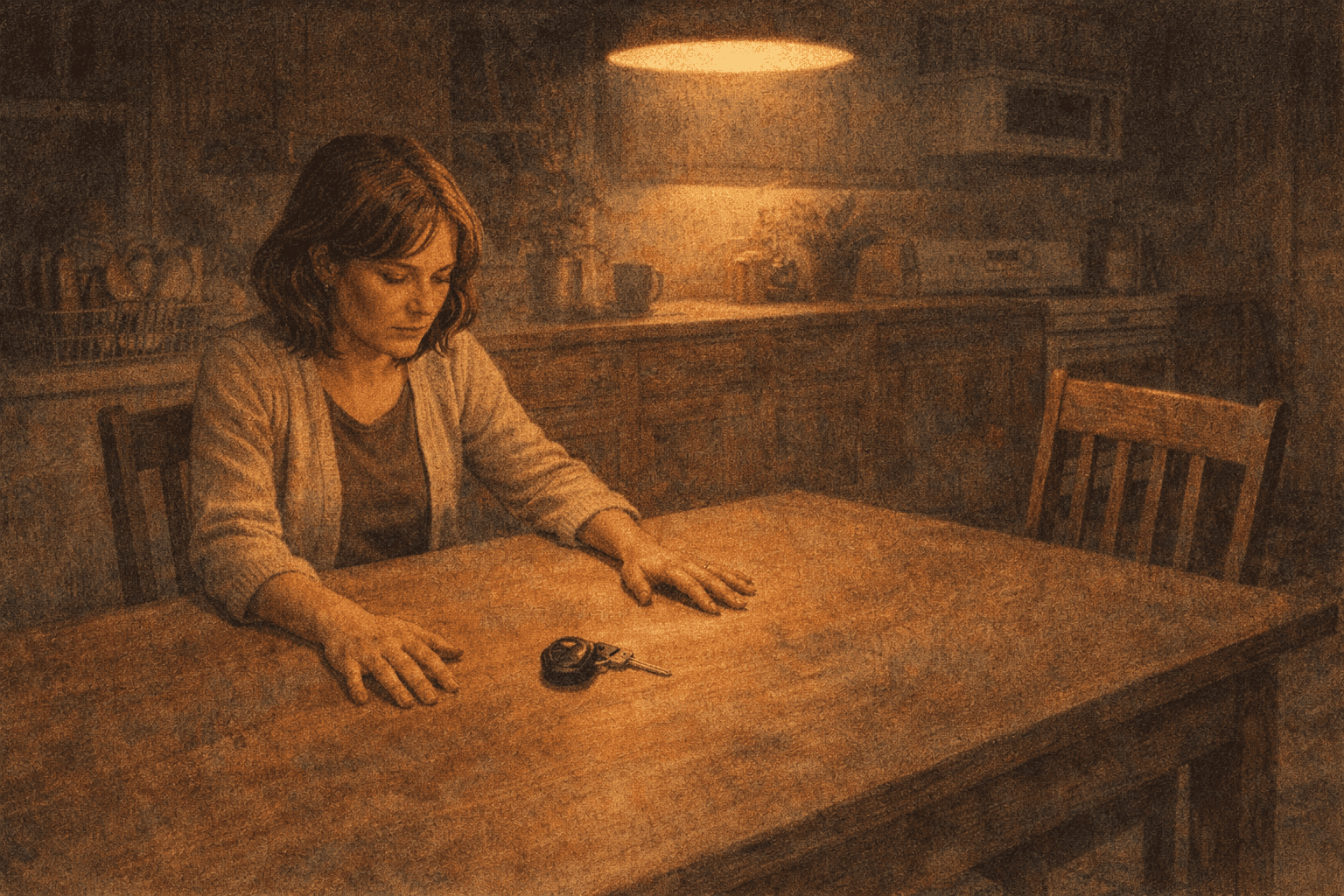

When consequences disappear, so does the urgency to do something different. The drunk driver who never loses their license keeps driving. The addict whose rent always gets paid never feels the weight of homelessness pushing them toward help. The son whose mother always calls in sick for him never has to face his boss. Enabling builds a cushion between choices and outcomes. And that cushion, however soft and well-intentioned, can keep someone comfortable in a place that should have become unbearable long ago.

The Difference Between Helping and Enabling

This distinction trips up almost every family we talk to. The line feels blurry because it is blurry. But here's a framework that helps.

Helping moves someone toward independence and responsibility. Enabling moves them away from it. Helping addresses a need in a way that builds capacity. Enabling addresses a need in a way that builds dependence.

Paying for treatment is helping. Paying off drug debts so they don't face consequences is enabling. Offering to drive them to a job interview is helping. Calling their employer to cover for them after they miss another shift is enabling. Setting a boundary and holding it is helping. Threatening a boundary and then caving when they push back is enabling.

The question isn't whether your action feels loving. The question is whether your action moves them closer to or further from taking responsibility for their own life.

Why Enabling Feels Like Love

Nobody enables out of stupidity. Families enable because they're terrified. Terrified that if they stop paying rent, their child will be on the street. Terrified that if they stop making excuses, the job will disappear and things will get even worse. Terrified that setting a hard boundary will be the thing that pushes their loved one over the edge.

And underneath all that fear is love. Real, desperate, exhausted love.

Enabling feels like love because it comes from the same place love comes from. It's the impulse to protect, to shield, to absorb pain on someone else's behalf. The problem isn't the impulse. The problem is that addiction twists everything. What looks like rescue from the outside is actually life support for the disease itself. You're not saving them. You're funding the very thing that's killing them.

Recognizing this isn't about feeling guilty. It's about seeing clearly. And seeing clearly is the first step toward loving in a way that actually helps.

Common Enabling Behaviors

Enabling wears a hundred different disguises. Some are obvious. Others are so woven into daily life that families don't recognize them until someone points them out.

Paying bills, rent, or debts that your loved one should be responsible for. Making excuses to employers, family members, or friends. Minimizing the severity of the problem to keep the peace. Avoiding hard conversations because you're afraid of their reaction. Bailing them out of legal trouble. Giving them money you know will be spent on substances. Letting them live at home with no expectations or accountability. Cleaning up their messes, literal or figurative, so they never have to face what they've done.

None of these make you a bad person. They make you a person who loves someone caught in addiction and hasn't yet learned that your love, channeled this way, is working against the outcome you're praying for.

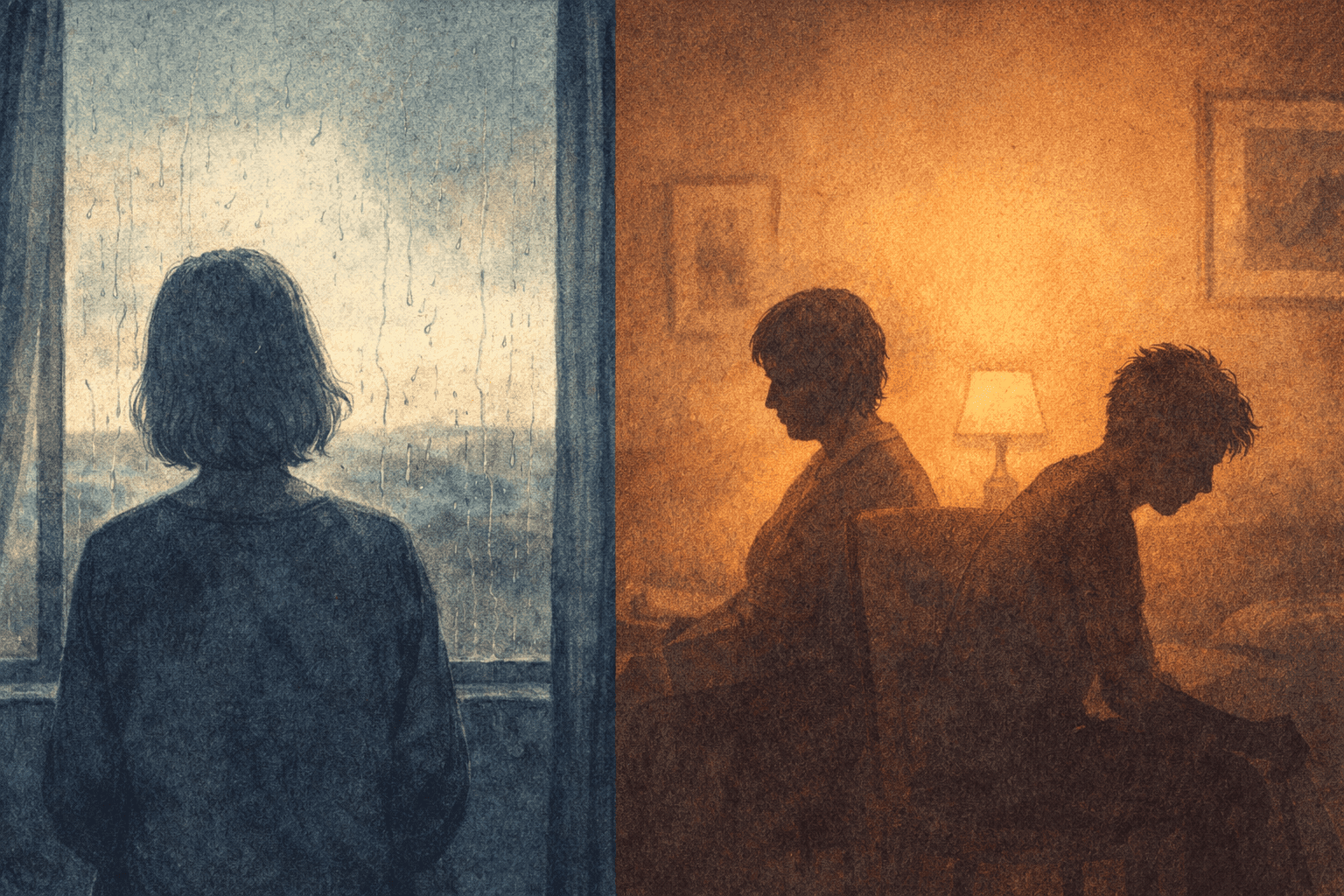

What Healthy Support Looks Like

Healthy support holds two things in tension: unwavering love and immovable boundaries. It says, "I love you and I'm not going anywhere" while also saying, "I will not participate in your destruction."

Healthy support means being honest, even when honesty is uncomfortable. It means letting consequences land instead of scrambling to soften them. It means offering real help, like connecting them to a program or driving them to treatment, while refusing to fund or facilitate the addiction itself.

For families ready to explore what real help looks like, understanding how faith-based recovery programs work can be a useful starting point. Programs like Teen Challenge exist specifically for people who have hit the wall that consequences create. When families stop cushioning the fall, sometimes the fall itself becomes the turning point.

That doesn't mean stopping enabling guarantees recovery. Sometimes people continue choosing destruction even when consequences are fully in play. Setbacks happen. Relapses happen. But at least you're no longer funding the decline. And at least your loved one is facing reality instead of a version of reality you've carefully edited on their behalf.

A Note on Grace

If you've read this far and feel a pit in your stomach, that's okay. Most families we work with carry enormous guilt once they realize how much of their helping was actually hurting. That guilt is understandable, but it's not useful.

You did what you did because you loved them. You didn't have the language or the framework to see it differently. Now you do. What matters isn't the years behind you. What matters is what you do next.

Recognizing enabling isn't an indictment. It's an invitation. An invitation to redirect the same fierce love that's been keeping them comfortable toward something that might actually set them free. You don't have to stop loving. You just have to start loving differently.

Taking the Next Step

Stopping enabling is one of the hardest things a family will ever do. It feels like abandonment even when it's the opposite. It requires the kind of strength that only comes from realizing the alternative is worse.

You don't have to figure this out alone. We've spent over twenty years walking with families through exactly these questions. We can help you think through boundaries, explore program options, and find support for yourself as you navigate this road.

Related Resources

How to Help Someone with Addiction: Complete Family Guide

What Is an Intervention? A Family Guide

Get hope in your inbox

GET HOPE IN YOUR INBOX

Encouragement, recovery insights, and ministry updates.

About the Author

Justin Franich

Justin is a former meth addict who went through Teen Challenge in 2005 and now serves families through resources, referrals, and real talk on recovery.

Continue Your Journey

Setting Boundaries for Recovering Addicts: A Family Guide

How to welcome your loved one home from treatment without enabling them-practical wisdom on communication, trust, and treating your adult child like an adult

Related Articles

How to Cope with Being Apart from My Loved One

Distance hurts-whether it's miles of separation or the emotional absence of someone living under the same roof. Both situations ache deeply. But neither one is hopeless.

Am I Crazy for Supporting the Addict I Love?

Friends say to quit. Family says to move on. They call you crazy for still hoping. But holding onto faith, hope, and love-the things Scripture says last forever-isn't foolish. It's foundation.

When the Confrontation Goes South

You finally said something. And it exploded. Anger, blame, withdrawal-different reactions, same purpose: control. When intervention blows up, you need boundaries. And boundaries require clarity about what's yours to carry.